In 2017, the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center was founded, dedicated to supporting the needs of those with substance use disorder. One of the first acts of the Grayken Center was to create a pledge that asked all hospital faculty and staff to commit to changing the way they spoke about addiction.

Why was an initiative devoted to changing language one of the first things the Grayken Center team did? Because when it comes to addiction, words matter. Words transmit stigma, and studies have shown that people with a substance use disorder often fear judgment and stigma in the health care system, which leads them to delay or avoid seeking treatment. In other words, the way we talk about people with a substance use disorder can change the way we treat people with a substance use disorder.

In 2010, John Kelly of the Recovery Research Institute conducted a study on the effect of language on stigma. He randomly selected doctoral level clinicians, including addiction experts, to hear two different vignettes. Both vignettes described a drug court situation in which an individual who had been told to remain abstinent had used alcohol or drugs and was about to face the judge again. Half of the individuals received vignettes in which the individual was described as a “substance abuser,” and the other half heard that the individual had “a substance use disorder.” Clinicians who heard “substance abuser” viewed the individual significantly more punitively, as having greater personal responsibility, being more to blame for his problems, and less deserving of treatment.

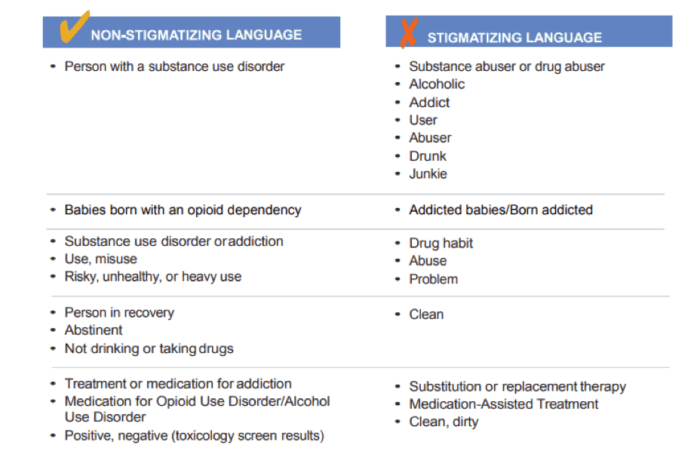

Despite the stark findings of that study, it’s not always obvious which words help and which words hurt. However, there’s a long history of research on language in medicine, and what researchers have found is that neutral, “person-first” language that focuses on the individual and not the condition is most effective. For instance, rather than saying that someone is their condition (e.g., diabetic, schizophrenic), we can say that someone has a condition. For individuals with a substance use disorder, this is particularly important, as a substance use disorder often is considered a moral or criminal choice, rather than a health condition.

In the past decade, many public health experts — including Richard Saitz, Sarah Wakeman, John Kelly, and others — have continued to develop non-stigmatizing language about addiction and share those findings with the general public. In January 2017, Michael Botticelli, then director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, issued a memorandum to the heads of all executive departments and agencies, encouraging them to change the terminology they used when discussing substance use and substance use disorders. Shortly thereafter, the Associated Press modified its widely used AP Stylebook to encourage reporters to choose person-first language when discussing someone with a substance use disorder.

And in May 2017, Botticelli joined Boston Medical Center as executive director of the Grayken Center, bringing with him a focus on reducing stigma. Thanks to his efforts, we launched the pledge with a hospitalwide letter from our CEO, Kate Walsh, and gained quick buy-in from hospital faculty and staff. Every year since, we’ve renewed our efforts to share the pledge, using our annual Recovery Month events and other hospitalwide gatherings to encourage our community to commit to using stigma-free language. We created a shareable version for other institutions to download as well. I’ve been a part of these efforts, and I hear firsthand how helpful the change in language is to creating a more welcoming, inclusive environment.

The impact isn’t limited just to our employees. Hospitals like ours employ thousands of people, many of whom may have experience with substance use disorder in their own family. They also are community centers, bringing together people from all walks of life. In these roles, hospitals can be a key catalyst for change. As employees unlearn the stigma they’ve been taught, they may share this view with family and friends and coworkers, changing the way the community at large thinks about addiction.